Why Limiting Methane Emissions Should Be Our Main Concern

- Constant Tedder

- Nov 3, 2021

- 3 min read

New research shows that limiting methane rather than carbon dioxide should be governments’ main concern at COP26. Earth.Org takes a closer look.

—

We’d freeze to death without the greenhouse effect (or just not exist at all), but thanks to heat-trapping molecules in the atmosphere, we live in an agreeable 14C average-temperature world.

Unfortunately, it so happens that the fossilised carbon fuels we use to drive our engines also release greenhouse gases, slowly but surely disrupting the benign 12,000-year climate that allowed humans to thrive.

Carbon dioxide is seen as the most important of these gases, despite it absorbing less heat per molecule than most of the others. This is because it lingers in our atmosphere for centuries longer, therefore committing us and the next generations to more warming.

We now find ourselves running out of precious time to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of staying under 1.5C, a threshold we will probably cross within a decade. The carbon dioxide we’ve emitted might already be enough to take us past it, if not within 10 years, then within the centuries it has left up there.

This is why it could be a good time to switch the focus from CO2 to another important protagonist: methane (CH4). It has been increasing just as relentlessly as CO2, with a higher potential to snowball out of control.

It is commonly described as having 28-34 times the warming potential of CO2, but this is a little misleading. With a 12-15 year lifespan, methane traps around 80 times the heat CO2 does over 20 years, dropping to 28-34 times over a century, the standard timescale.

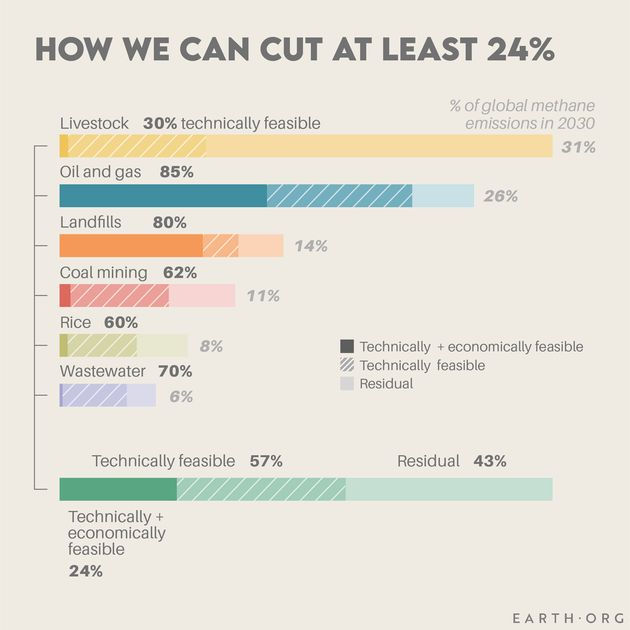

Indeed, limiting methane emissions could be an excellent solution to effectively curtail short-term warming. A recent study led by Ilissa Ocko of the Environmental Defense Fund found that there are many available, yet underutilised strategies to reduce methane emissions throughout a range of industries.

According to them, pursuing all of the technically feasible measures now could slow warming by 30% in the next decade. On geological timescales, that is near-immediate impact, and the authors argue it is far preferable to the current focus on long-term, carbon-centred policies.

In fact, action towards limiting methane emissions is likely to be slowed or delayed while decarbonisation and net-zero are given priority, despite the former’s feasibility and the latter’s unclear outcome.

Admittedly, methane has benefited from a lack of visibility to escape governmental action. In the oil and gas industry, its emissions are often fugitive, unintentionally leaked out of fossil fuel infrastructure and poorly quantified. Similarly, those from landfills are significant, yet poorly monitored.

Crude measurement techniques may have been to blame, but satellite technology recently changed the game. Academic, private and non-governmental organisations can now access a literal eye in the sky to flag undeclared or underestimated methane sources.

Researchers from Harvard found that emissions in Texas and New Mexico were twice government figures, while the french satellite analysis company Kayrros SAS flagged a huge methane leak from a Russian pipeline owned by Gazprom just yesterday.

Administrations now armed with a wealth of information that was previously unavailable should see the opportunities in limiting methane. The question remains whether they will divert enough attention and effort from the all-important decarbonization effort to make significant changes. Let’s hope definite progress isn’t sacrificed for a stubbornly held long-shot.

Featured Photo by John Bakator on Unsplash.

You might also like: The 9 Biggest Fast Fashion Statistics

Comments